Experts Uncover a Lost WWII Submarine and an 80 Year Old Mystery

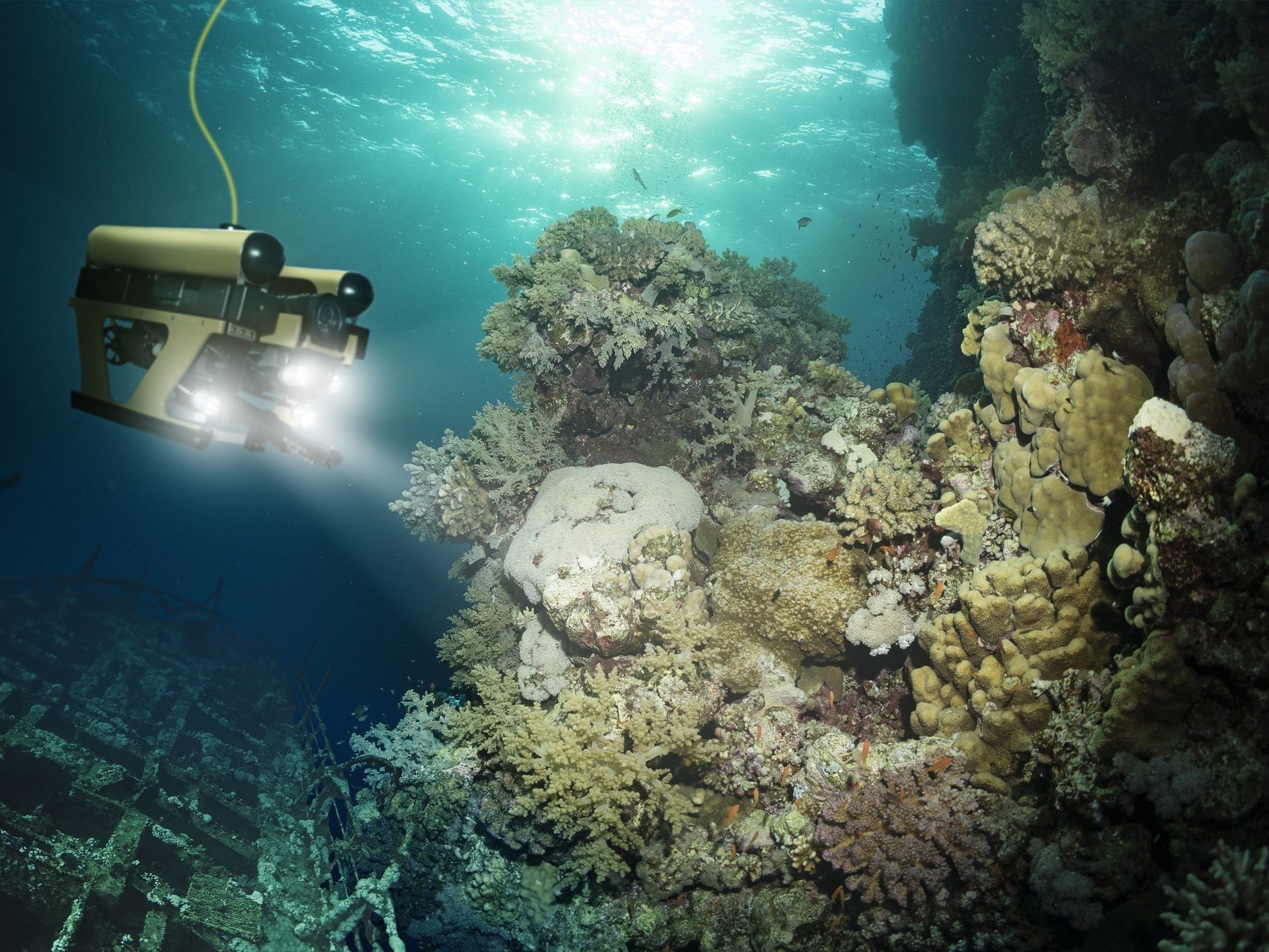

It was the summer of 2019, and a crew of modern explorers known as “the Lost 52 Project” led by Tim Taylor, were searching the open seas on a mysterious mission.

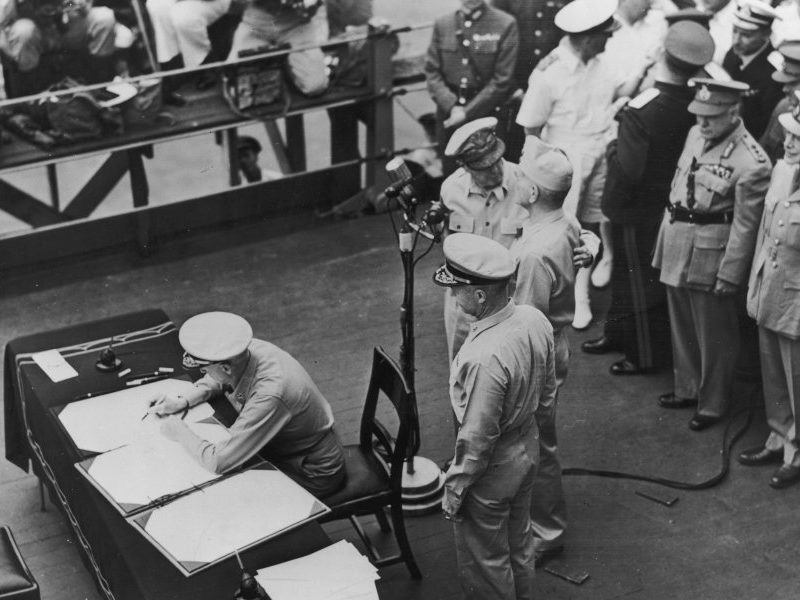

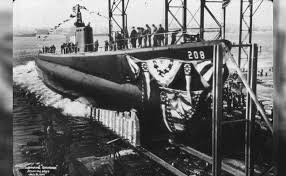

An almost 80-year mystery is laid to rest right around Veteran’s Day with the discovery of the “USS Grayback” (SS-208), one of the most famous and decorated World War II submarines, that disappeared in 1944 with 80 crew members onboard.

They’re using an unmanned underwater vehicle to look for the sub and its crew, but as the underwater drone travels through the endless deep blue sea, it surprisingly malfunctions. The team retrieves the UUV to only find out inconspicuous data that compels them to go to uncharted depths of the ocean.

What they uncovered next will give you goosebumps.

The U.S.S. Grayback

The U.S.S. Grayback commenced its final voyage on a 1944 winter morning in Hawaii. It was destined for combat patrol in the East China Sea.

Image: forummarine.forumactif.com

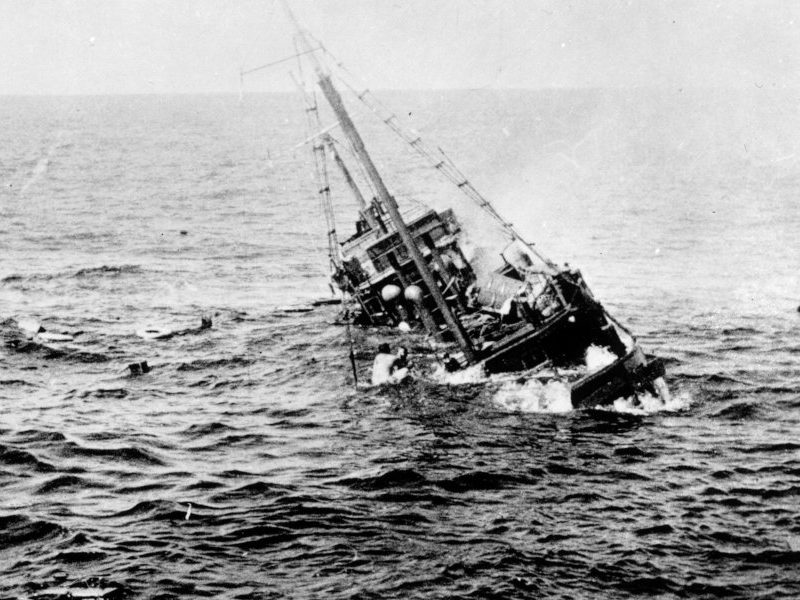

The ill-fated voyage seemed to start productively. About a month after setting out, they reported that they’d sunk two Japanese vessels and damaged two others.

The Last Patrol

Things seemed to be going to plan when, the next day, the Grayback radioed news that they had done damage to the Asama Maru and sunk the Nanpo Maru tanker.

Image: Corbis via Getty Images

Their missile reserves nearly depleted. They were ordered to head for the Midway to restock. This is when their luck began to turn.

The Communique

They were expected to arrive on March 7 1944, but the day came and went with no sign of the submarine.

Image: Daily Herald Archive/SSPL/Getty Images

Days passed and hopes dwindled but were not lost. When the Grayback still hadn’t appeared or contacted the base station, they were forced to declare the sub and its crew missing in action.

Major Losses

The decision to abandon hope for the return of the wayward ship was an agonizing one. With a crew of about 80 sailors, the human toll was truly devastating.

Image: telemundo.com

The disappearance of the craft itself was also a major loss for the allies, given its past nine successful expeditions.

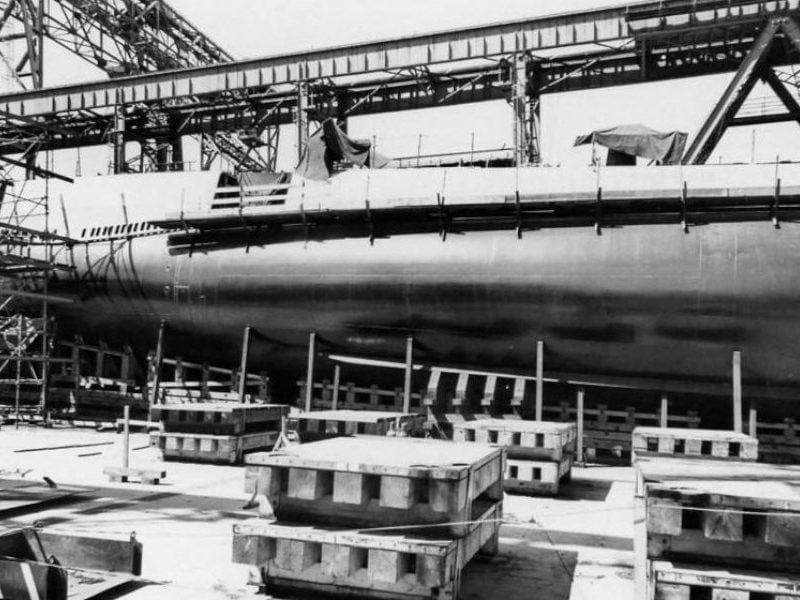

The Electric Boat Company

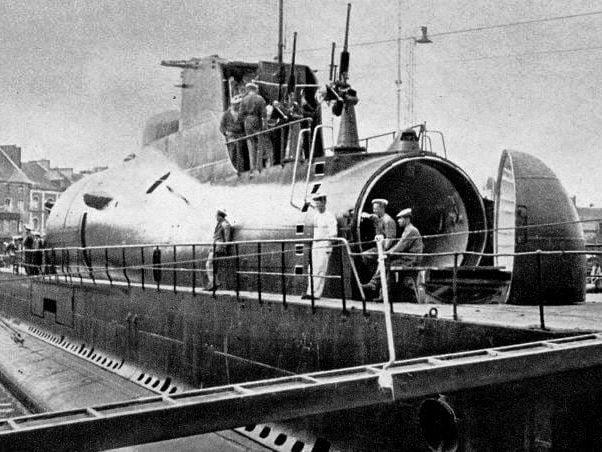

The Grayback began its life in 1940 at Electric Boat Company in Groton, Connecticut, a shipyard where its strong metal frame was first assembled.

Image: H. Armstrong Roberts/ClassicStock/Getty Images

Around 40 years earlier, in 1900, this same shipyard also produced the very first submarine commissioned by the U.S. Navy, the U.S.S. Holland.

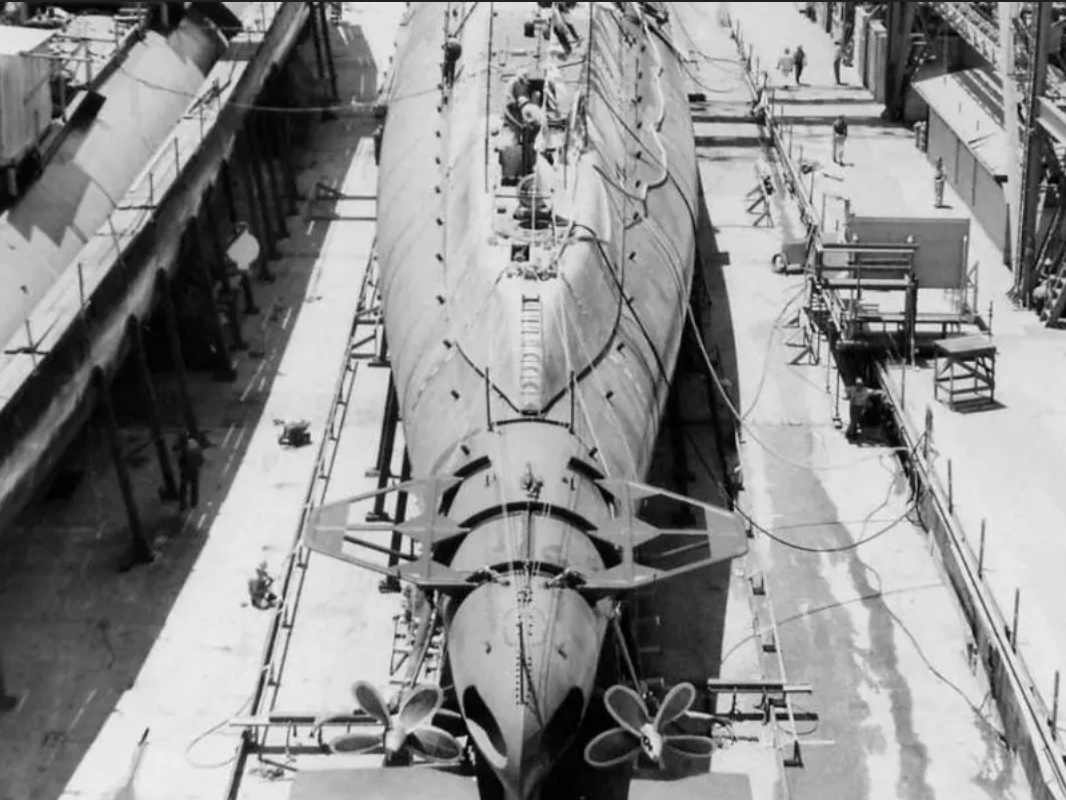

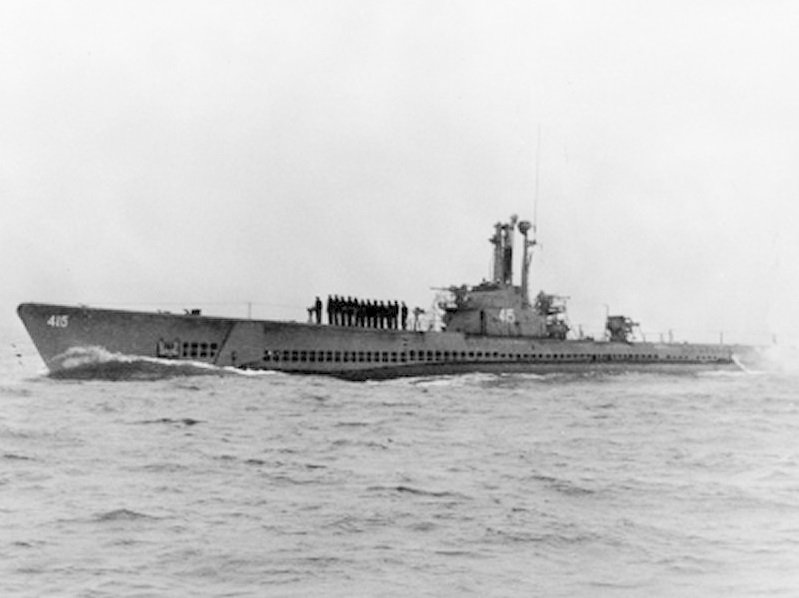

The Tambors

In the years following, the Electric Boat Company churned out lots more submersible ships.

Image: facebook

This includes the sub that would eventually become the subject of this tale, a Tambor-class submarine. They built 12 of these ships, only five of which ended up surviving to see the end of the war.

The Sub's Features

Like her metal siblings, The Grayback could travel up to 21 knots (39 km/h) and could reach a range of 11,000 nautical miles.

Image: Darryl L. Baker

This enabled them to travel all the way to Japanese territory and back. Pretty impressive for a vehicle that could displace 2,410 tons of water.

The Living Conditions

Though it was heavy, it wasn’t exactly roomy. At 307 feet long and 27 feet wide, it couldn’t have been a comfortable place to live for weeks.

Image: Corbis via Getty Images

Especially when a crew of 80 is squeezed into a space for 60, as we have learned was the case on the fateful 1944 voyage.

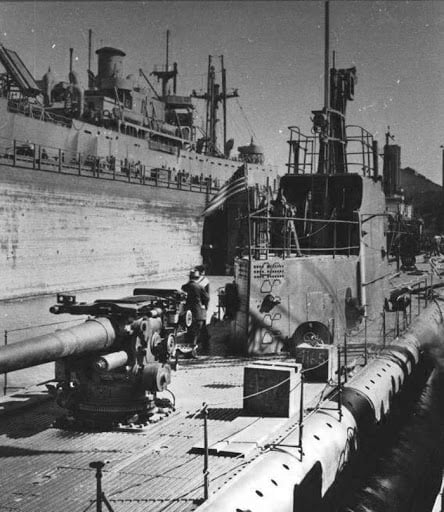

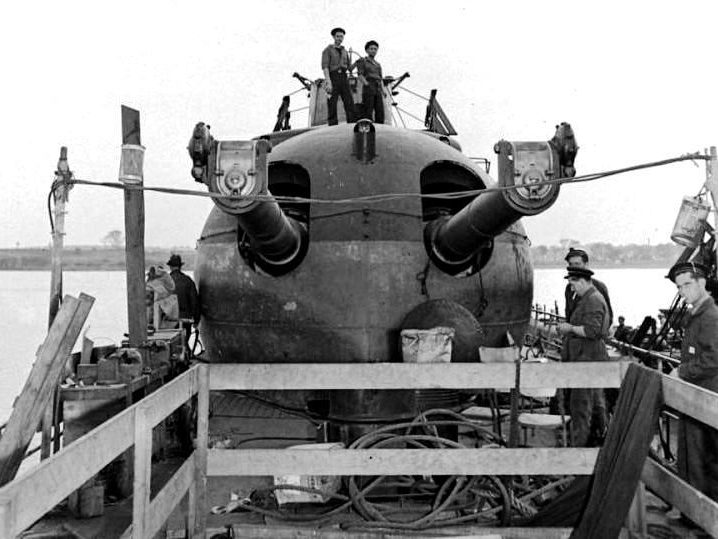

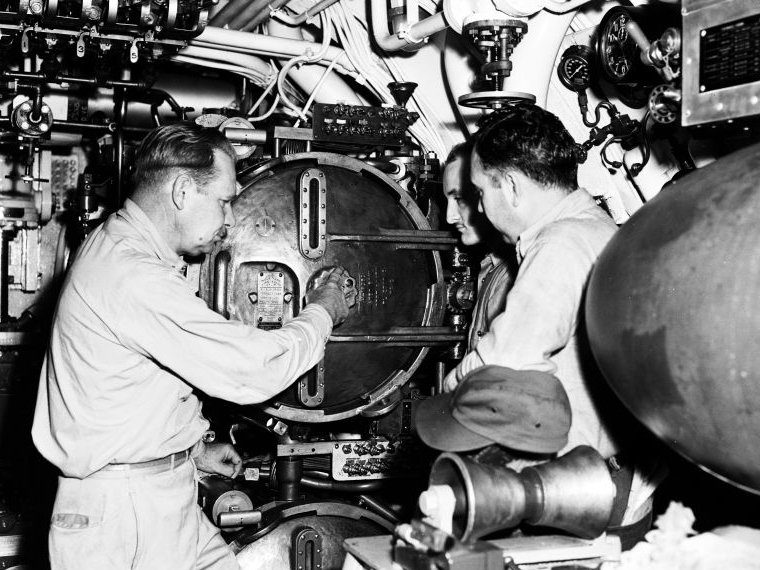

The Arms

Comfort, of course, is far from the highest priority on a vessel carrying 24 torpedoes. This ship was designed for combat, and it was well prepared.

Image: ww2db.com

The floating bastion also sported two large cannons and a 50 caliber machine gun, making it quite a formidable foe in aquatic battles.

The Shakedown Cruise

In order to determine that the Grayback was ready to take on combat, it was required to undergo what’s called a “shakedown cruise.”

Image: Corbis via Getty Images

This was essentially a trial voyage with simulated working conditions to test the performance of the craft. It passed and was subsequently ordered to begin patrolling the seas.

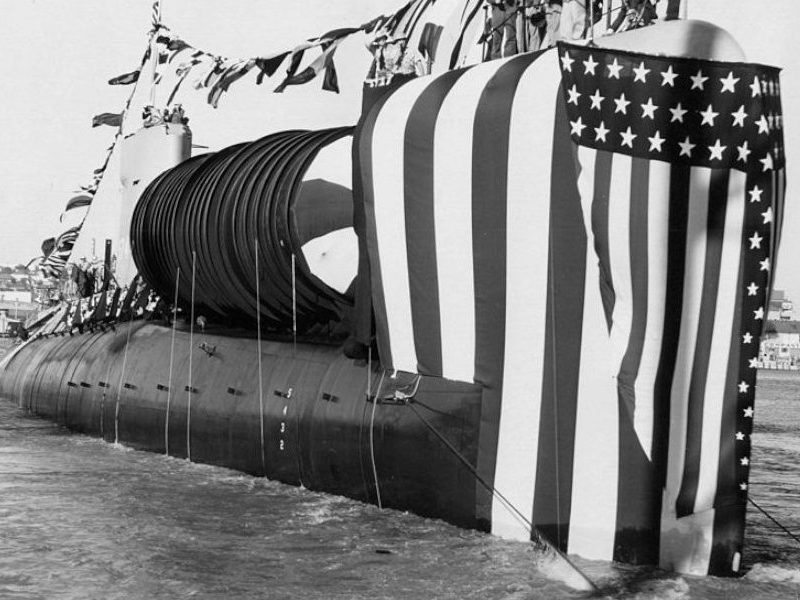

The Construction & Launch

Workers toiled for ten months constructing the impressive submarine. Its first launch was on the 31st of January, 1941.

Image: michaelbwatkins/Getty Images

Its official commission into the U.S. Navy followed in June of that year. Five months later, the U.S. would become the next country to join the fray in WWII.

The Beginning of the War

Then, as we all know, the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 catapulted the U.S. right in the middle of the worldwide conflict.

Image: picbear.com

By 1942, the Grayback was headed for Hawaii, and then soon after – battle. The brand-new sub was about to hit the ground running.

The First Patrol

The ship’s first wartime mission began on February 15, 1942. They were bound for Guam and Saipan, two islands in the pacific that had been targets for the Japanese army.

Image: U.S. Coast Guard/Getty Images

There the crew encountered their first enemy, another sub, which fired two torpedoes at the Grayback. Fortunately, they missed.

The Close Call

After being pursued for four days and just barely escaping the enemy, they continued along their path. The close call still remained in their minds, however.

Image: Darryl L. Baker

A few weeks later, on March 17, they saw combat again. This time, they emerged victorious, having sunk the Ishikari Maru, a cargo vessel.

The Tough Times

The missions that followed were difficult and fraught with hazards, but ultimately proved worthwhile for the crew of the Grayback.

Image: Corbis via Getty Images

Though they endured rough seas and often shallow waters infested with enemy ships, they managed to actually do some damage to various foes. They were essential to maintaining territory for the allies.

The Christmas Attack

On December 7, 1942, the Grayback headed for the coast of Australia on its legendary fifth tour. Firstly, one of the medics performed a successful emergency appendectomy on a crew member while underwater.

Image: Naval History and Heritage Command

Just a few days later, on Christmas, the ship surfaced and took four enemy crafts by surprise, sinking them handily.

The Rescue

The sub went on to claim more victories, and even ended up participating in a rescue mission for some airmen who were stranded on a nearby island.

Image: William P. Boyle

They surfaced under the cover of night and smuggled the stranded soldiers to safety. For their heroic rescue, the skipper was awarded the Navy Cross.

The Encounter

Even after all that, the events of the tour still weren’t over. The Grayback continued onward to damage a number of Japanese ships.

Image: Keystone/Getty Images

However, on January 17, they entered into a conflict with a destroyer that managed to sink 19 depth charges into the sub, causing dangerous leaks requiring repair.

Has the U.S.S. Grayback’s luck run out?

The Broken Radar

After limping home and receiving some much-needed repairs and upgrades, the sub was given the go-ahead to venture out on an another tour.

Image: U.S. Navy

Unfortunately, the radar, which had just been installed as part of the ship’s refurbishment, failed to function. That meant they couldn’t find a single ship.

More Victories

On tour number seven, the dauntless Grayback made its way to Brisbane, Australia on a much more successful journey. The element of surprise served the crew well.

Image: Darryl L. Baker

They successfully sank two different enemy ships and seriously damaged a destroyer before being ordered back home for some upgrades and maintenance.

The Eighth Tour

With all its knobs and switches polished and primed, the newly souped-up submersible was ready for tour number eight.

Image: U.S. Navy

It was also carrying a new commander, John Anderson Moore, sailing with its companion the U.S.S. Shad, a Gato-class sub. They were destined for the Midway Atoll in the North Pacific Ocean.

The Wolfpack

Once they had reached the island, the two submarines met up with yet another friendly vessel called the U.S.S. Cero.

Image: U.S. Navy

Together they formed what is commonly called a “wolfpack.” This turned out to be a pretty accurate moniker as, together, the three boats formed a highly lethal team.

Successful Teamwork

As a unit, the ships reported that they had sunk 38,000 tons of enemy assets and damaged another 3,800.

Image: Keystone/Getty Images

With the help of their teammates, the crew of the Grayback succeeded in sinking two adversary ships. Skipper John Moore, like his predecessor Stephan, was given the Navy Cross for their efforts.

The Tenth Patrol

After the success of its previous mission, they set out again on what would be their penultimate mission – this time to the East China Sea.

Image: Keystone/Getty Images

They quickly entered a skirmish, taking out four ships with all the torpedoes they had on board. It was another victorious journey for the U.S.S> Grayback.

The Final Mission

After a quick turnaround in Pearl Harbor, the submarine was deployed on its final mission – the ruinous one which would ultimately end at the bottom of the ocean.

Image: Naval History and Heritage Command

Back then, no one suspected that it would end in tragedy. Given the vessel’s history, hopes were high for another productive tour.

What could possibly go wrong?

The Battles Won

It started out quite well, with the Grayback reporting that they’d sunk another two cargo ships and damaged two others.

Image: U.S. Navy/Interim Archives/Getty Images

The next morning initially brought more good news; another ship sunk and damage done to a second.

The Mistaken Place

That message was the last anyone heard from the crew of this doomed vessel for many years. About 75, to be exact.

Image: Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images

At the time, it was assumed that the sub had gone down off the coast of Okinawa, a small island in the Ryuku Island archipelago south of mainland Japan.

Lost in Translation

The assumed location of the Grayback was based on records from the Japanese Navy that ended up being mistranslated by the Americans, getting the position wrong by about 100 miles.

Image: Los Angeles Examiner/USC Libraries/Corbis via Getty Images

This misunderstanding meant that the downed sub’s actual location remained a mystery until well after the war was over.

The Explorer

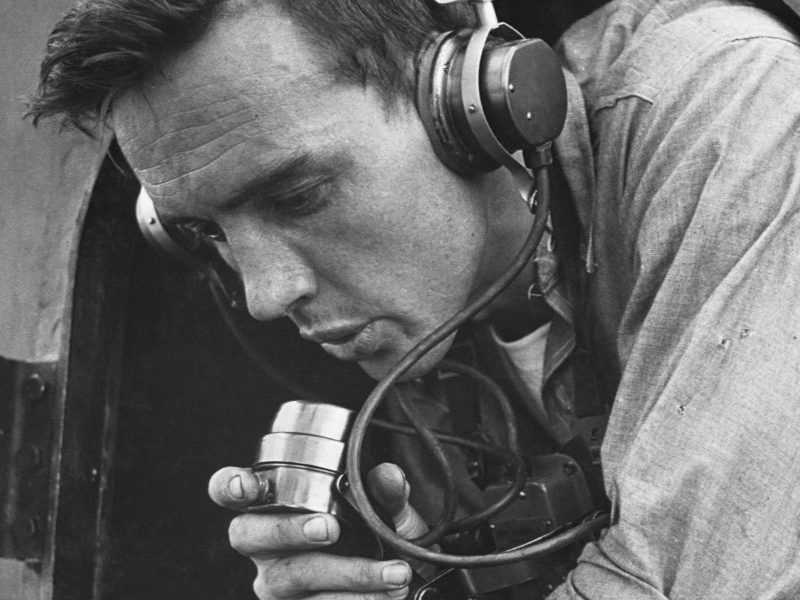

Enter one Tim Taylor, a modern-day Cousteau who has spent years exploring the world’s oceans. He’d made a career of uncovering the many mysteries of the sea.

Image: atese/Getty Images

With that goal in mind, he founded the Lost 52 Project. This organization sought to locate lost crafts from WWII using cutting edge technologies.

The First Find

The project began after Taylor successfully orchestrated the discovery of another lost sub – the U.S.S. R12.

Image: via Twitter/USS Bowfin (SS-287)

It was a much older craft, commissioned back in 1919. It sank with its crew aboard in June of 1943 during a routine training exercise. 42 lives were lost in the tragic accident.

The R12

The R12 had once been a combat sub like the Grayback, but much earlier. In fact, it had actually been removed from the Navy’s main roster of ships in 1932.

Image: U.S. Navy

However, when war once again threatened the U.S., the sub was refitted and drafted back into service in July 1940.

Good as New

On its first voyage after being recommissioned, the R12 was sent to the Panama Canal in order to protect it from approaching enemies.

Image: Jared_Sislin_Photography/Getty Images

The crew worked there for around a year. They were then ordered back to Connecticut where they patrolled the Atlantic waters until Pearl Harbor brought them back to Panama.

The Failed Excercise

By 1943, The R12 was no longer completing patrols, but was rather used as a training vessel at a facility in Key West.

Image: vlastas/Getty Images

One exercise proved to be too much when, unexpectedly, the craft began to take on water. Attempts were made to save it, but it was too late.

The Lucky Few

As it took on more and more water, the sub rapidly plunged 600 feet into the sea with all but five of the crewmembers trapped inside.

Image: Stocktrek/Getty Images

The ones who survived were only spared because they were out on the deck when the incident occurred, and they were swept off and rescued.

The First Photos

R12 languished beneath the waves for nearly seventy years before Tim Taylor’s team discovered its wreckage using a robotic submersible.

Image: S_Bachstroem/Getty Image

This enabled them to capture the first images of the lost sub since it had sunk so many years earlier. They also gathered important data so as to prevent another tragedy.

The Goal

With the mission to find the R12 a resounding success, Tim Taylor founded the Lost 52 team and pledged to discover even more lost submarines.

Image: A. E. French/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

52 subs were reported lost during WWII, and Taylor and his team resolved to find them all in honor of the over 3,000 sailors who lost their lives serving their country.

The Discoveries

Over the course of ten years, the squad of sub-seekers discovered the location of five more downed vessels in various parts of the Pacific.

Image: U.S. Navy

Using advanced technology, they’re able to document and subsequently create realistic renderings of their discoveries. This helps them uncover the mysteries these wayward ships can hold.

The Real Reason

They also collect samples and detritus from the wreckage to aid in their scientific studies for future missions.

Image: YouTube/Ocean Outreach

Ultimately, though, their objective is to uncover the truth and bring peace to the families and loved ones of the venerated sailors who lost their lives in these catastrophic wrecks.

The Other Fish

Lost 52 has also discovered two other ships from the WWII era. One, the U.S.S. Grunion, was discovered near Kiska, Alaska..

Image: USN/USNI

The U.S.S. Stickleback, which was found near Honolulu, Hawaii, was actually lost during the Cold War. It collided with another sub during training and sank.

Examining Old Reports

Lost 52’s hunt for the Grayback began with a thorough examination of the original reports detailing the lost sub’s whereabouts.

Image: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The team’s Japanese translator and researcher was able to re-translate the documents and discovered the error. This gave them new data to work with and pointed them in a new direction.

The Mistake

The error was transcribed from a radio report sent from Naha, Okinawa to Sasebo in Nagasaki. It was sent out just a few days after the Grayback’s final dispatch.

Image: Three Lions/Getty Images

The report described the true fate of the Grayback. It began with a standard Japanese bomber plane, a Nakajima B5N.

The Bomber

The plane took off on a routine patrol, and encountered an American submarine sailing on the surface. It didn’t hesitate to attack.

Image: Marseas/Getty Images

The plane dropped a bomb onto the unsuspecting submarine, blowing a hole in the hull and sending it sinking to the depths. No survivors were noted from the wreck.

The Real Location

The most crucial part of the message, however, was the explicit location of the downed craft.

Image: U.S. Navy

Upon careful review, it turned out the coordinates were different than they thought. The original estimation was shockingly off by about 100 miles, meaning past searches had no chance of finding the lost sub.

Will the remains of the U.S.S Grayback finally be found?

The Underwater Hunt

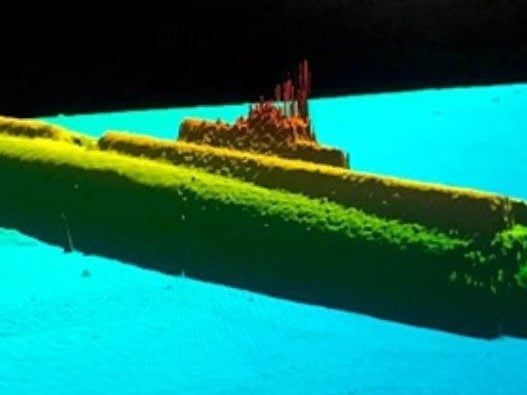

Now that the team had solid data, they could begin the search in earnest for the lost Grayback.

Image: YouTube/Ocean Outreach

After lots of combing through the nearby waters, the wreck of the ship was finally discovered. Surprisingly, the hull was still mostly intact after being submerged under the waves for over 70 years.

The Human Toll

As one could imagine, discovering the wreck was all at once thrilling and somber. They’d finally found what they were looking for.

Image: YouTube/Ocean Outreach

At the same time, this was the final resting place of 80 sailors, and the reality of that loss weighed heavily on the minds of the Lost 52 team.

The Survivors' Families

Another group of people were also affected by the discovery of the Grayback’s remains. These were the relatives of the sailors who were lost that day.

Image: YouTube/Ocean Outreach

Bringing solace to these families was at the heart of Lost 52’s mission. By uncovering details about what happened, they could help tell the sailors’ stories.

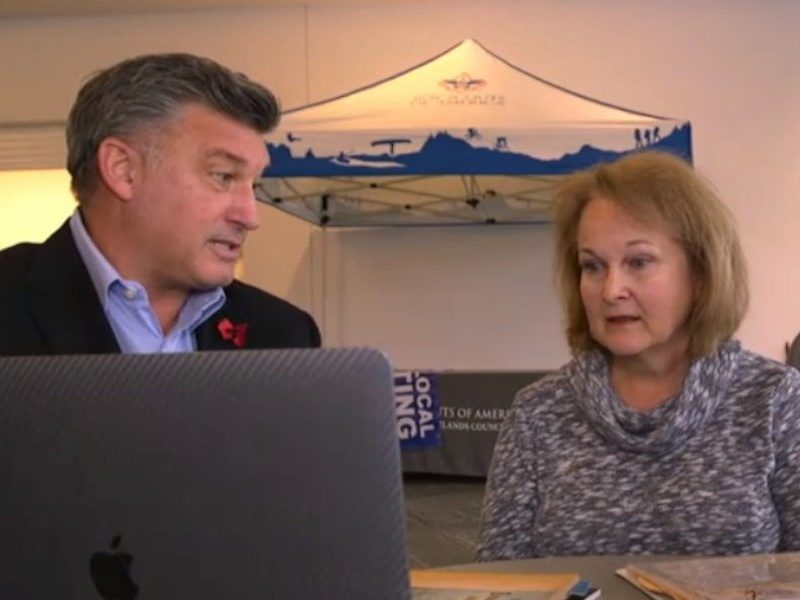

The Peace of Mind

A family member of one of the crew described the initial shock of the ship’s discovery, as well as the feeling of peace that the news later brought.

Image: YouTube

Simply knowing, rather than wondering, what had happened to their loved ones enabled them to move forward and heal from the tragedy.

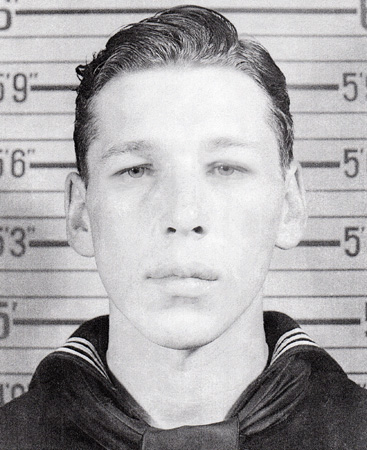

Motor Machinist's Mate, Third Class- Leslie Harold Leaf

The gift of closure was given to the family of lost sailor Leslie Harold Leaf after the announcement of the discovery of the Grayback. According to Leslie’s family, he was “really good natured.”

Image: Facebook

Leslie’s niece said that he was called “Beefy” as a nickname. Everything that Leslie’s niece had learned about him was through storytelling, as she was never able to meet her uncle before he passed.

A Bit About Leslie

When Leaf was 19 and had graduated from high school he decided to join the Navy. Apparently, Leslie had joined the Navy after Pearl Harbor had occurred.

Image: Facebook

“I don’t think Grandpa was very happy,” Delores, Leslie’s niece said. Sadly, Delore’s grandfather had every right to worry about his son, and for a long time no one in their family knew what had become of Leslie.

Lost At Sea

All Leslie’s family knew, along with the other 79 crew members aboard the fated Grayback, was that he had been lost at sea. There was no sense of closure for the family members for the one that they had lost.

Image: Facebook

It was an amazing Veteran Day’s surprise to receive news of the whereabouts of where their loved one had been lost at sea.

“Always Waiting” for Leslie

The family members recalled how their grandmother had never stopped carrying a torch for her lost at sea son.

Image: Facebook

Apparently, the mother never took the service flag down from her window. “She was always waiting for uncle Harold [Leslie] to come home.”

Leslie Was Awarded

Leslie received the honor of the Purple Heart and ranked as Petty Officer Third Class. His specialty was Motor Machinist’s Mate Third Class.

adverts.ie

The Purple Heart is a United States military decoration awarded in the name of the President to those wounded or killed while serving

Petty Officer First Class- William Jack Brasch

William Jack went by Jack since his father was William Joseph. Jack was born in 1920 in Washington state and grew up in Yucaipa and Mentone. He attended Redlands High, where he was a track star, and graduated in 1938. He immediately enlisted in the U.S. Navy.

After training in San Diego, he served on the battleship California, then a submarine tender, the Fulton. His next assignment was the Grayback.

Remembering Jack

Chuck Brasch, Jack’s half brother is still taking it in. The retired science and pottery teacher from Chaffey High in Ontario shared his brother’s Purple Heart, awarded posthumously in 1946.

A book, “U.S. Submarine Losses,” prepared by the Navy was sent to sent to the family in 1948.

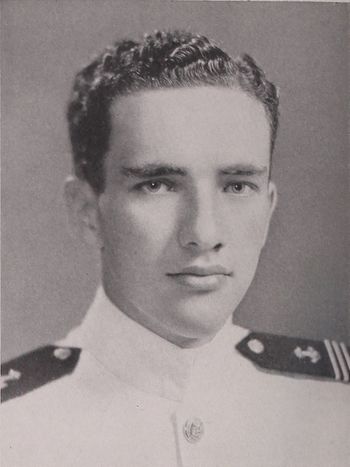

LTJG- Melvin C. Phillips

LTJG- Melvin C. Phillips widely known as Mel would argue with everyone on any subject. And usually you could be sure he was right. He was commander of 16th Company for the first set, was manager of the baseball team, and was a member of the Lucky Bag staff.

Although usually quiet and reserved, Mel would argue with everyone on any subject. And usually you could be sure he was right. Mel was awarded the Purple Heart Navy Unit Commendation Medal, American Area Campaign Medal, American Defense Service Medal with Fleet Clasp, and the Asiatic-Pacific Area Campaign Medal fior her service.

Honoring The Veterans

Along with having the special gift of finally finding out the true nature of how they had lost their loved one on the nationally celebrated Veterans Day, they also felt it was important to highlight everything that he and others had done.

Images: ww2db.com

“He gave his life for our country and freedom,” Delores said. “It is a good thing they found it.”

The Remains Underwater

A plaque was erected for the members of the Grayback submarine for the family to commemorate their life and death.

Image: Facebook

The submarine sits underwater. The deck gun was made from the primary wreckage. The wreck also had severe damage near the conning tower, which matched the Japanese’s report of a direct hit in that area.

The Second Sub

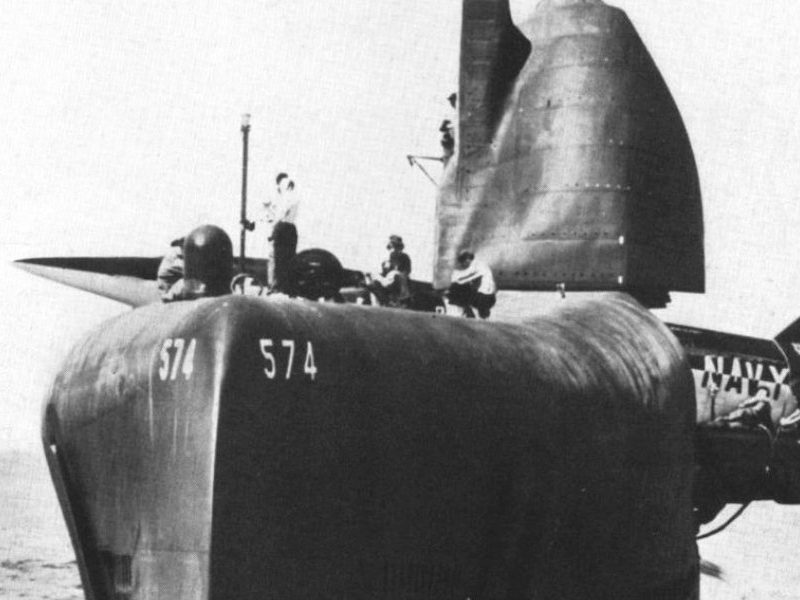

The legacy of the Grayback lives on, as a second sub with the same name was commissioned years later – in 1957.

Image: USN

It first launched in San Diego, California. In a nod to the original craft, the widow of John Moore, the skipper from Grayback I, sponsored its first launch.

A Happier Ending

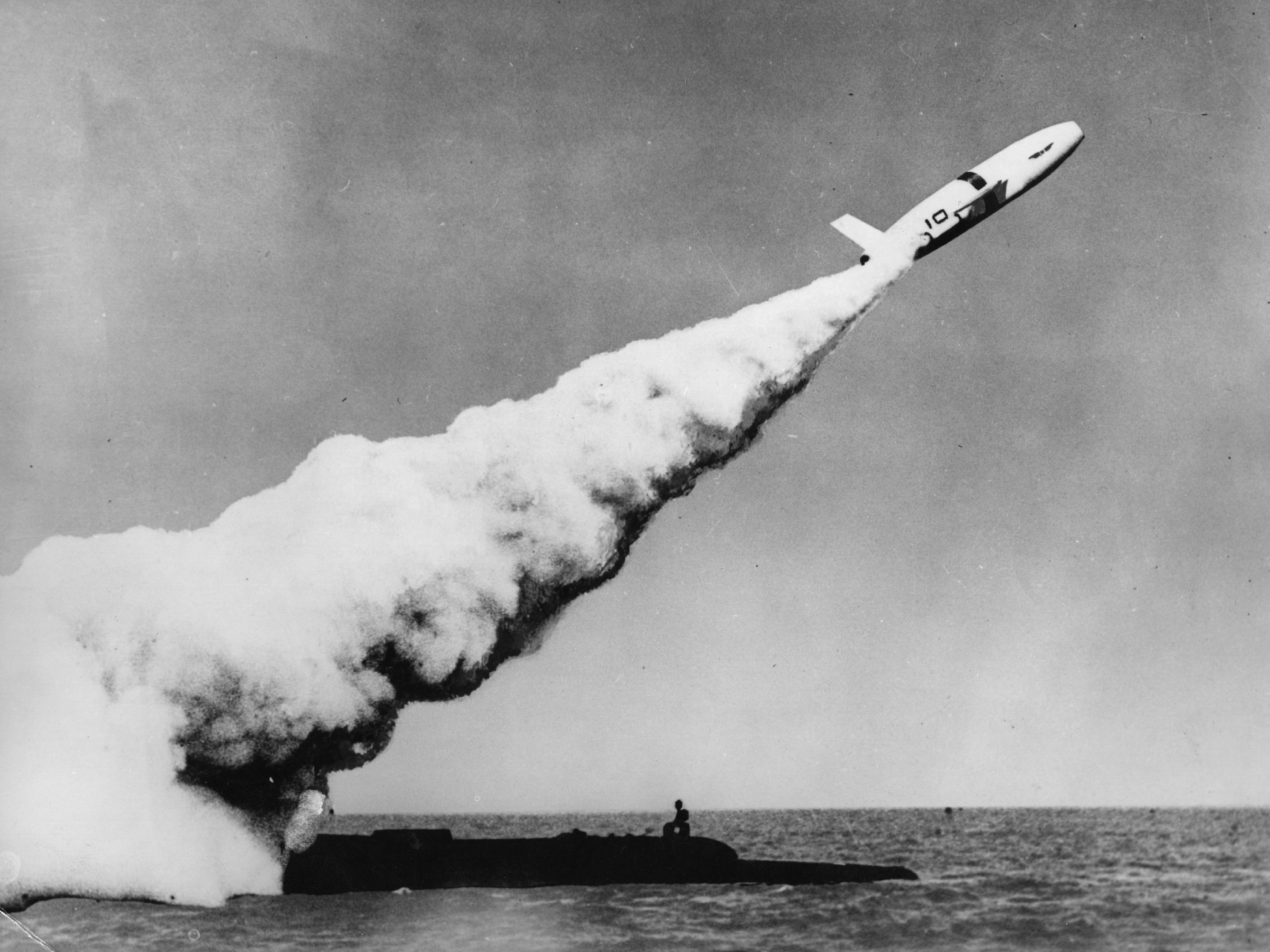

Unlike the original, this new sub’s birthplace was on the west coast, in Vallejo, California. It was leaner, meaner, and more powerful than the original.

Image: Keystone/Getty Images

The updated craft employed new technology like a guided missile system, and successfully patrolled waters for 27 years before it was officially decommissioned from service.